Edward Burman, The Templars, Knights of God: The Rise and Fall of the Knights Templars, Destiny Books, Rochester, Vermont, 1986.

In 1099 the knights of the First Crusade conquered Jerusalem and a portion of the Holy Land. The Order of Knights Templar was founded in Jerusalem nine years later and was originally comprised of only nine members. The knights of the Order received favored treatment from King Baldwin II who provided them with lodging in his own palace adjacent to the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. The full name of the new order was the “Order of the Poor Knights of the Temple of Solomon.” Count Hugh of Champagne traveled to the Holy Land to become a member and the Count of Anjou became another backer.

Bernard of Clairvaux, founder of the flourishing Cistercian Order, took the lead in drawing up rules for the Knights Templar. Before he became a monk, Bernard had been a knight himself. The new rules of the Order included that the members were to pray together often, live in common, take their meals in silence, make only “holy conversation”, remain celibate, and eat meat no more than three times per week and on holidays. No wine was permitted with meals.

The Knights Templar expanded rapidly in France and England. Pope Innocent II issued a decree that freed the order from all authority other than that of the Pope, making the Templars virtually autonomous, a rarity in medieval society. Another Papal decree the following year allowed the Templars to construct their own churches. By 1147, the Templars had become rich enough for King Louis VII of France to turn to them for loans to finance the Second Crusade.

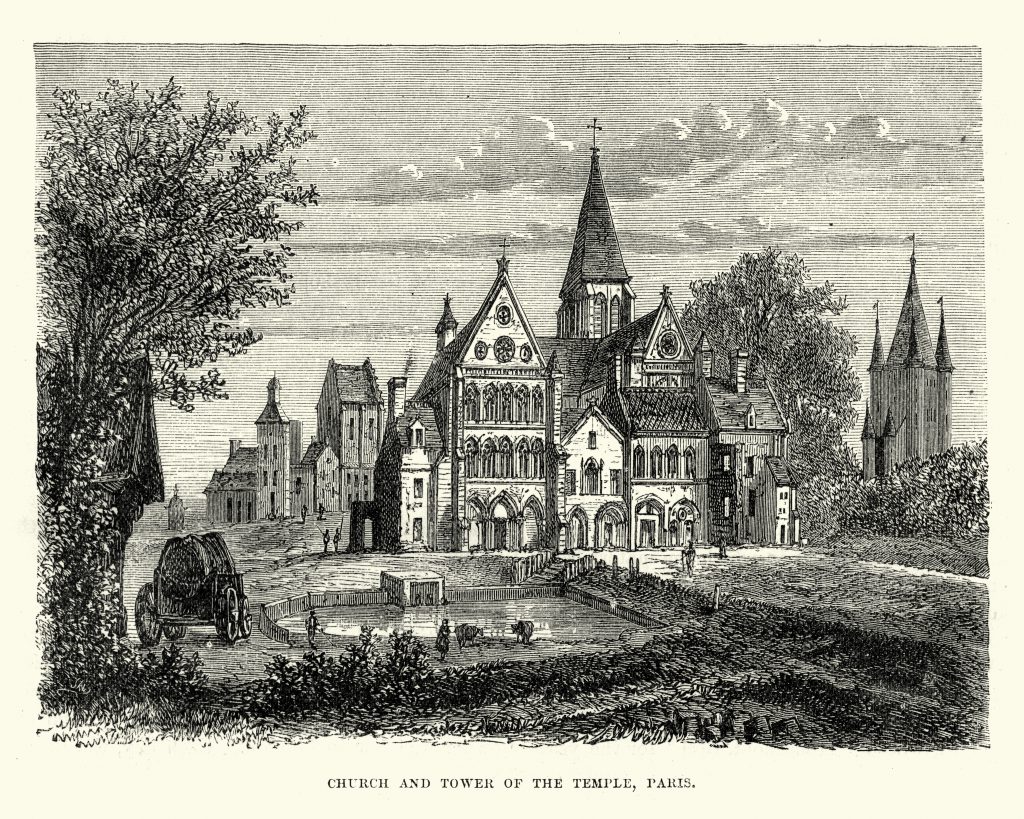

In the following century and a half, the wealth and power of the Templars continued to grow. Impressive Templar castles were raised on promontories in France and the Holy Land and in central locations in Paris and London. In Jerusalem, the Order took over and restored expanses of what had been the Temple of Solomon where they erected their own new palace, cloister, and other buildings. By the late 12th century, the Knights Templar were among the most important bankers and lenders in Western Europe, making use of financial skills acquired in the more advanced Holy Land.

During the 13th century, they began operating their own large fleet in the Mediterranean. The Order, Burman tells us, “became a great banking agency whose branches in the European capitals, in Jerusalem, and in the majority of eastern centers handled all manner of exchange transactions with enormous profits.”The London Temple became the “medieval precursor of the Bank of England”. In 1204, King John deposited the royal crown jewels in the London Temple for safekeeping. By the late 13th century, the “reputation of the Templar vaults was almost legendary.” During the 13th century, they became, in addition, bankers and tax collectors for the Pope.

Simultaneously the Templars took a leading role in the development of commercial agriculture in Europe. They took an active role in reclaiming vast tracts that had been marsh or fen. On their estates, a contemporary wrote, “the Templars employ farmers and agricultural laborers, shepherds and millers, gardeners and artisans but overall they exercise the same control.” By 1300, the Order of the Temple had become a major economic power.

In 1187, Jerusalem fell to the forces of Saladin and Islam. The effort of the Third Crusade, led by the kings of England and France and the Holy Roman Emperor, to retake the Holy City was not successful. In July 1191, the Crusaders were forced to surrender their stronghold at Acre. At the close of the century, however, Islamic forces steadily drove out the remaining Crusaders. Acre, previously retaken and their last citadel fell again in 1291.

By the 14th century, the Templars had been long accused by their detractors of having grown excessively wealthy. They were suspected also of having, during their time in the Levant, grown too close to, and sympathetic to, the adherents of Islam. During the first decade of the 1300s, King Philip the Fair of France was determined to consolidate and expand royal power. On Friday, October 13, 1307, he struck at the Templars who were believed to be harboring a vast treasure horde. Philip’s chief weapon was the accusation of heresy against the Order. The arrest warrant issued by Philip accused the Templars of “terrible and inhuman crimes and practices”, but did not specify what these were.

In Paris, 138 members of the Order, including Master Jacques de Molay, were arrested, turned over to the Inquisition, and tortured to get them to confess to the wrongs they were accused of. It is impossible to know if any or all of these charges were true. The arrested Templars continued to strongly deny their innocence. After recanting confessions made under torture, fifty-four Templars, including many leaders, were burned at the stake in a field outside Paris. In March 1314, the Master of the Order Jacques de Molay, still protesting his innocence, was burned to death at the stake in front of Notre Dame. In other countries, however, many Templars survived.

The Inquisition against heretics had the unfortunate practice of burning the writings and records of those it deemed as enemies. The inner beliefs and practices of the Templars remain unknown. The extent to which they actually did or did not engage in mystical and occult rituals outside the usual rites of the Church will likely never be certain. The Templars’ two centuries in the Middle East may have opened them to teachings from the Islamic world, including from the mystical Sufis. Bernard of Clairvaux, closely connected to the Templars, was a fervent admirer of the mystical Biblical Songs of Solomon and was drawn also to the kabbalistic schools that flourished in Troyes, close to Bernard’s own monasteries.

What is clear is that the great flowering of gothic art and architecture, from the mid-12th to the early 13th century, coincided with the zenith of Templar wealth and power. For the flourishing Templars not to have been a source of funds for the construction of the multitude of gothic edifices simultaneously rising up in France at that time would have been strange indeed. Beginning in the 17th century, the first Freemasons in England would cite the Templars as among their spiritual predecessors. Belief in the connection between the Templars and Freemasons persisted as Masons took a central role in the French Revolution of 1789. Immediately after King Louis XVI was beheaded in the Place de la Republic in 1793, an anonymous voice, likely a Freemason, shouted out loudly, “Jacques de Molay, thou art avenged!”

Next: The Templar Revelation