Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince, The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ, Touchstone, New York, 1997.

Despite Lynn Picknett’s and Clive Prince’s admirable efforts, much about the Knights Templar remains a mystery. The Order of the “Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon” was officially established in 1118 in the aftermath of the First Crusade which had succeeded in re-taking the Holy Land for Christianity. Clive and Prince don’t, unfortunately, have a trove of newly unearthed Templar archives to share. In the early 1300s, the Templars would be declared by the Pope to be heretics and, as with other “heretical groups”, all of their writing that could be rounded up by the Church authorities was burned. This has made the task of attempting to rediscover who and what the Templars really were, and especially their religious beliefs and practices, extremely difficult for historians.

The accomplishment of Picknett and Prince is to set the still legendary Knights Templar within the larger context of the broader tangled and tumultuous history of Christianity, and especially of other “heretical” groups, beliefs, and practices during their time. During its first 1500 years, Christianity encompassed many diverse threads and currents of heritage, perspective, and belief. That promoted and enforced by the “official” Catholic Church was only one of these. Picknett and Prince reveal a few new secrets about the Templars. By setting out in detail the larger environment in which the Templars grew and thrived, along with their later vicious suppression as heretics, we can attempt educated guesses about their directions, faith, and what they may have been involved in.

Picknett and Prince begin this story back in the time of Jesus with the very different “branches” of Christianity that had begun to emerge during Jesus’ own lifetime and the first centuries that followed. For over two hundred years, the Templars held key outposts in the Holy Land, carried out excavations beneath the ruins of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, and developed a trading empire that stretched from one end of the Mediterranean to the other. Their focus on the Temple of Solomon wasn’t surprising. It was, after all, right in the name of the order itself. The Templars are believed to have also provided major financial support for the construction of the breathtaking wave of new gothic cathedrals that swept across Northern France and Northern Spain during the 12th and 13th centuries.

In carvings on a pillar of Chartres Cathedral’s North Portico, the “Gateway of the Initiates”, Templar knights are depicted battling in the First Crusade, excavating and recovering the Ark of the Covenant, and then carrying it off toward its new resting place led by an angel with God hidden overhead in a cloud. Inscribed there too was the cryptic admonition in Latin, “You shall work by the Ark.” (See photos on Mysteries of Chartres Cathedral page). The Templars, however, kept a well-defined distance between themselves and the Roman Catholic Church.

Picknett and Prince believe the Templars emerged from out of a fundamental split in the “Tree of Christianity” that dated back to Jesus’ own time. The “Church of Peter and Paul” that had followed had transformed both God and Jesus into strictly fearsome authority figures on the Roman imperial model. In 325 CE at the Council of Nicea, presided over by Emperor Constantine, other branches of the original Christian teachings were deemed “heretical” and thus forbidden. The most widespread of these were the strong currents of “Gnostic” beliefs and believers who also claimed that their own branch of Christianity dated directly back to Jesus and to the Essenes before him.

Gnostics maintained that Jesus had been a human being who could be emulated, not a Roman-type “god”. What Jesus had been, they held, all of us had the potential to be. Jesus was viewed as a model to be followed, not a harsh ruler in the heavens to be submissively obeyed. All human beings, the Gnostics taught, could become one with God, hear God’s voice inside, and join in God’s work as Jesus had done. Such beliefs, according to Gnostics, had not in fact begun with Jesus at all but were integral to a shared spiritual heritage that extended to the ancient Jews, Greeks, Egyptians, and Persians. The Templars refused to worship the symbol of the crucifix and may have rejected the entire official story of the crucifixion. They would not kneel before what had been a Roman torture device.

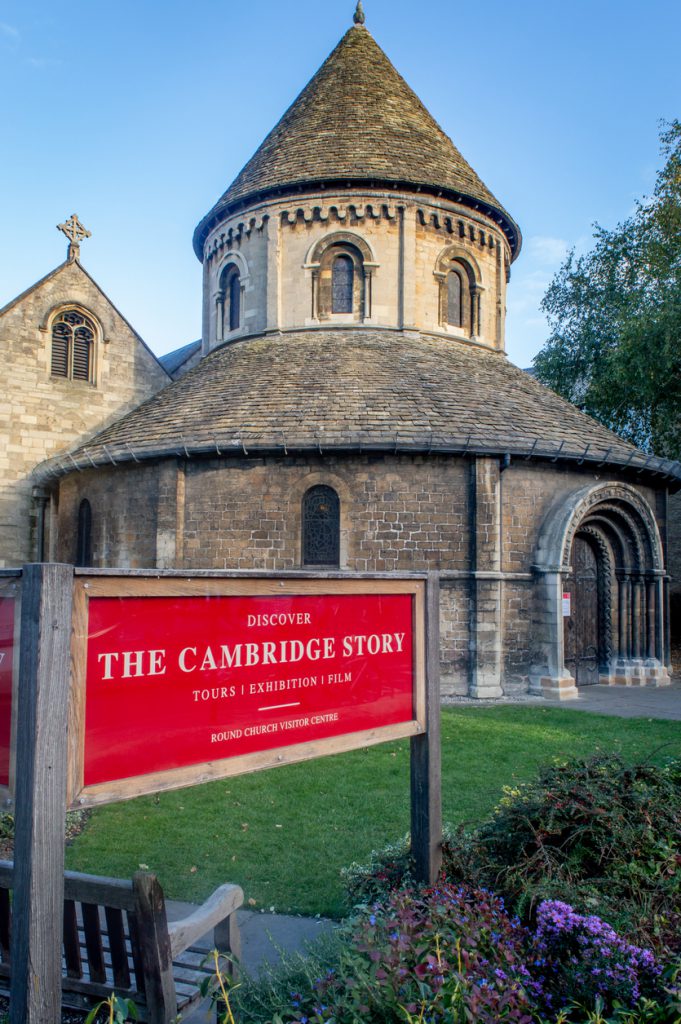

Instead, the Templars’ own churches were often round, intended as a reflection, most probably, of the unity and “one-ness” of the divine creation. Even Chartres, though cruciform in shape, never included any crosses as part of its original design. If the ambulatory behind the altar is included, the interior form of a gothic cathedral actually more resembles an Egyptian ankh, a symbol of life, than a Christian crucifix. The Templars did display a red cross proudly on their tunics and battle flags, but it was always an equilateral form, splayed wide at each end, that did not much resemble a crucifix.

Such mystics were viewed by the official Catholic Church, however, as heretics and their beliefs as a terrible threat. If every human being could communicate directly with God, could, in a sense, even become God, the authorities feared, how could order, obedience, and the rule of the few over the many be maintained? Following, 325 CE, large numbers of those preaching and practicing “heresy” were rounded up, tortured, and burned alive. Religious freedom within the newly Christian empire was viciously suppressed. Alternative currents persisted stubbornly, however, underground. It is from this milieu of a potentially very different kind of Christianity that the Templars first emerged in 1118.

The Templars rigorously maintained their distance from the Pope and the “official” Church, harbored many secrets they weren’t willing to reveal, and required their members to maintain that silence. From their outset, however, the Templars were closely linked with Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who was also the founder of the flourishing Cistercian monastic order. The Templars were supposed to live, to a large extent, like monks as well, but be “warrior monks.” Bernard, himself was in many ways a gnostic at heart who rejected the corruption and falsity of the official Church. Through his expanding network of thriving, elegantly simple Cistercian Abbeys, he sought to restore a spiritual focus and depth of aspiration that had become lost.

To avoid the torture rack and the stake themselves, however, Cistercians, Templars and even Bernard himself needed to be tight-lipped about the new alternative Christianity they were attempting to forge, one they believed adhered far more closely to the actual teachings of Jesus. Their many decades in the Holy Land had made a strong impact on the Templars as well. It is widely believed they established connections with Sufi mystics there that led to new insight into the relationship between God and the created world and led them even farther from the orthodoxies of the Catholic Church. These connections contributed as well to their deepening fascination with architecture and sacred geometry and desire to build upon those principles in France as well.

Southwestern France had become a center for Templar strongholds and activities. From there, they expanded their ties with the Jewish communities of Southern France, Catalonia, and Andalusia. As these connections grew, their attraction to the paths of alchemy and kabbalah may have increased as well. Both were doorways into the magical secrets of the ancient world, a focal interest of the Templars since their beginnings. The original Templar knights had come from Champagne and Troyes, its capital, had long been a center of kabbalistic studies. Saint Bernard, though himself a leading figure in the Church, also actively delved into kabbalah in his hometown of Troyes.

There was, in addition, another strand central to this story causing growing concern back in Rome. This other underground stream running through Christianity also dates back to the life of Jesus himself, his relationships with John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene, and their roles in the first years of the Church. There is considerable evidence that Mary Magdalene, usually scorned as a reformed prostitute, may instead have been Jesus’ primary and most important disciple, the one who best understood his teachings and attempted to carry them on after his death. She may also have been, Picknett and Prince believe, not only his sexual consort but even his wife. She may even have been the mysterious woman who anointed Jesus in his role as Messiah.

Mary Magdelene herself is widely believed to have arrived in Southern France after the death of Jesus and remained there for the rest of her life. If true, she most likely landed in the busy Roman ports of Marsala (Marseilles) or Narbonne, located further west and which would develop one of the strongest Jewish communities in France. In the South of France, many churches are dedicated to her and her feast days elaborately honored. Her strong association with the Egyptian goddess Isis is reflected in the intriguing, long prominently displayed “Black Madonna” of Chartres.

Alongside the suppression of women and sexuality by the established Church, other very different directions may have continued underground in which women were fully equal to men and possibility of “sacred sexuality” embraced. Though the Templars were supposed to be celibate, there were also women members of the order who were not knights. There is clear evidence of the practice of sacred sexuality in some of the heretic communities of the Middle Ages, especially in the Rhine Valley. Alchemy and sacred sexuality, called “Tantra” in the East, were sometimes explored together as interlinked aspects of the transformational path.

There is yet another piece central to this already complex picture. In 1209, King Phillip Augustus of France and Pope Innocent III ordered an army of French knights into the province of Languedoc in Southwestern France on what would become known as the “Cathar Crusade” or “Albigensian Crusade”. Their goal was the complete eradication, including by mass murder, of the largest, most well-established heretic community in France, known as the Cathars or Albigenses. Over the next ten years, French knights slaughtered up to 100,000 peaceful Albigensions in an epic scale of blood-letting even for the Middle Ages.

By 1209, the Cathar offshoot of Christianity had been steadily expanding in the Languedoc for two hundred years. The sense of crisis felt in Paris and Rome was triggered by the expansion of the Cathars beyond the Languedoc. In a growing part of France, Cathar communities, beliefs, and teachings were displacing the hold of the established Church. In the 1200s, most Europeans toiled as oppressed, impoverished, and often hungry serfs, while Church prelates and even local priests often lived far more comfortably and had become widely viewed as hopelessly decadent and corrupt, nothing more than greedy spiritual imposters. Within the official Church, barely a shadow seemed to remain of what Jesus had actually taught or what he had intended. Even the words of Jesus were never translated into the local languages, but remained only in Latin, so that only very few could even know them.

The Cathars had first arrived in France as itinerant preachers from the Balkans before 1100. They had brought with them a more Eastern, mystical, egalitarian, and ascetic way of life that, to many, seemed far closer to original early Christianity. They had gained the protection of the powerful Count Raymond of Toulouse who had become almost a Cathar himself, triggering even more severe alarm in Paris and Rome. In Cathar communities, all property was held in common, vegetarianism was widely embraced, preachers received no special treatment, and had to follow strict rules of personal purity. The Pope dispatched Saint Bernard himself to the Southwest to find out what was going on and Bernard came back impressed, with nothing but good things to say about the Cathars.

To the king and Pope, however, the Cathar movement had become seen as a dangerous threat, a challenge to their power that needed to be eradicated, which it was in a series of shocking military campaigns. The details are gruesome. Puzzling and far from clear, however, is the role of the Templars in the Cathar Crusade. In the early 1200s, the Templars were also at the height of their wealth and power. Did they join in that devastation and slay down Cathars as well? Did they refuse to participate or even oppose what was going on? Did they aid the Cathars against the royal army sent to eliminate them or at least attempt to? No one seems to know for sure.

Picknett and Prince set out in detail how strongly and concurrently, or near-concurrently, these several heretical currents of Cathars, Templars, the “cult of Mary Magdalene”, alchemy, and kabbalah all ran in Southwestern France in the early 13th century, and melded together in a rich and potent stew, a yeasty bubbling broth of a very different kind of Christianity. Exactly how they intersected and interacted with each other is, however, far less clear. We do know that following the destruction of the Cathars, Templars remained in the Languedoc in surprisingly large numbers for the next hundred years, until the bloody hand of the suppression of “dangerous heresies” fell on them as well. The extremely gory events of the early 1200s in the Languedoc were also, sadly and ironically, occurring simultaneously as a very different expression, or arm, of the Church was completing creation of the glories of the greatest of gothic cathedrals to the north in the Ile de France.

Next: The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages