Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution, Penguin, London, 1975.

Christopher Hill was a Professor of History at Balliol College, Oxford, and the author of half a dozen of the most important works on 17th-century English history. The middle decades of the 17th century found a rapidly changing Britain in crisis. Older traditional ways of life were fast being displaced, but there were fierce differences, and then bloody battles, over the new form of society that would replace them. “From 1645 to 1653,” Hill writes, “there was a great overturning, questioning, revaluing, of everything in England. Old institutions, old beliefs, all values all came into question.” It was, in Hill’s words, “a period of glorious flux and intellectual excitement” when the old world was viewed as “running up like parchment in the fire” and “literally everything seemed possible.”

The intense ferment that wracked England in those years was fostered by the fact that “economically, financial hardship from the years from 1620 to 1650 was among the most terrible in English history.” The “New Model Army” assembled and led by Generals Cromwell and Fairfax, that rose against Charles I, was, “no mere mercenary army but the people in uniform, closer to their views than those of the gentry or Parliament.” Free discussion and debate within this unique force, Hill writes, “led to a fantastically rapid development of political thinking.”

According to Hill, a central cause of the Civil War that erupted in 1642 was the effort by the monarchy and large-scale aristocratic landowners to push “common people” off of, and out from, the extensive stretches of forests, heaths, mores, fens (marshes), and wooded glens where during past centuries, and into Elizabethan times, they had been able to eke out a subsistence livelihood while retaining their independent way of life. These were free, proud though poor, “master-less” men and women with no desire to be exploited as tenant farmers or turned into wage slaves. A pivotal issue of the mid-17th century was “enclosure” for their own personal profit, by the King, aristocrats, and wealthy, of what had long been reaches of undeveloped “commons” available for the habitation and use of all. In a heritage dating back to Robin Hood, these still wild expanses were populated as well by:

“…thieves who specialized in robbing those who ground down the faces of the poor, enclosers of commons, usurers foreclosing on land, ‘builders of iron mills that grub up forests with timber trees for shipping’, and cheating shop-keepers and vintners.”

Many areas where enclosure and eviction were being pressed most forcibly became centers of rebellion against the Crown. Large landowners were also carrying out “disforestation”, leveling the groves that had provided homes, subsistence, shelter, and freedom to the many “humble folk” who had dwelled there for so long. In Cambridge shire, Oliver Cromwell took one of his first actions in support of this insurrection when he led local “fenmen” in resisting the draining of the marshes surrounding Cambridge that had provided them with nourishment and an unfettered life for generations.

As the military uprising against the King gathered strength, Parliament’s New Model Army became a center of revolutionary thought and demands. Its leaders were known as “Levelers” and “Agitators.” Hill records that:

“There had been nothing like this spontaneous outbreak of democracy in any English or continental army before this year of 1647. The rank and file organized themselves from below, led by the yeoman cavalry regiments. Petitions were drafted, some of them dealing with political as well as military matters. By the summer of 1647, the Agitators also had their own printer, a Leveler and were at the height of their influence (and) linked with their civilian counterparts.”

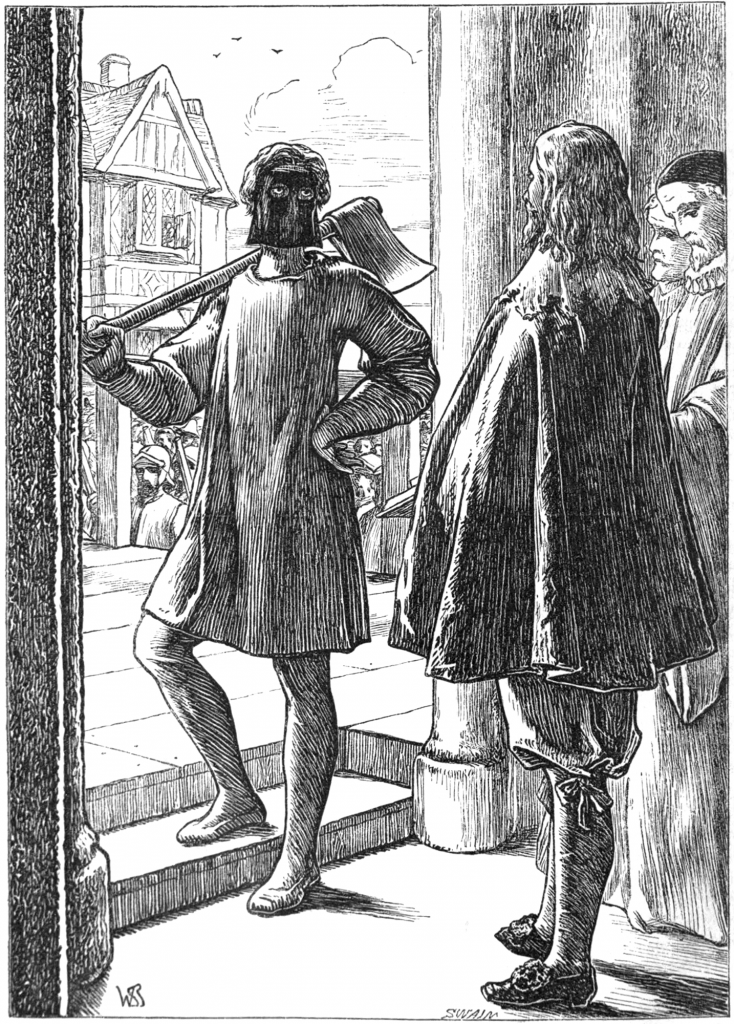

Amidst the over-heated political climate of the Civil War, it didn’t take long before Levelers and Agitators were pressing hard for a very different kind of England. Violent battles erupted within the Army between elements that sought a far more egalitarian transformation of Britain and conservatives who wanted to restrain the power of the King while retaining the underlying social structure. In these fierce, increasingly bloody, skirmishes followed by full-scale military engagements, the conservatives, led by Cromwell, managed to retain the upper hand. One cost was a large number of martyrs slain down for the revolutionary cause.

The “Diggers” emerged in the midst of this ferment. They moved back into common areas from which they had been displaced, began to turn over and fertilize the soil, and attempted to sew crops on what had been common lands, resulting in small autonomous Digger colonies spread across many parts of rural Britain. They sought to “dig” these shared lands to grow their own food and favored communal cultivation over private plots. Landowners, however, saw these Digger colonies as a grave threat. By the final years of the 1640s, they had succeeded in forcibly suppressing all of them.

The English Civil War, and the execution of Charles I that resulted in 1649, had checked the power of the monarchy. Among many in the humble classes, their aspirations for more fundamental underlying change had extended far further. For the upper and middle classes, however, “Leveler” became a term of scorn and abuse. A contemporary writer observed that even, “John the Baptist would have been despised too if he had called himself a Leveler.” Egalitarian leader Gerrard Winstanley declared that Jesus Christ himself had been the “Head Leveler” and cited passages from the New Testament as supporting “community of property.” By 1650, the Diggers were calling for confiscated lands of the crown, church, and royalists to be turned over to the poor to cultivate. Large accumulations of private property, and especially possession of vast inherited properties, were denounced as “anti-Christian.”

Alongside the Diggers, Levelers, and Agitators, a radical wing of the Puritan movement wanted freedom from the kinds of personal restraints long enforced by the established church. Chief among these, surprisingly from a contemporary perspective, was sexual freedom. In early Quaker meetings, less clothing was sometimes experimented with along with occasional full public nudity and the right to have multiple sexual partners. If all human beings, their reasoning ran, had the ability to be at one with God and the spirit of Jesus, then all actions taken in such a state of communion could be viewed as expressing that innate inner divinity, rather than as sins. These new freedoms were loudly advocated by lay preachers, called “Ranters”, in many Puritan churches. A considerable number of 17th-century radicals, according to Hill, also possessed strong interests in alchemy, mysticism, and Hermeticism. Some believed these studies could help reveal how to reconstruct the world in accord with over-arching divine laws, rather than merely reflecting the greed, selfishness, and brutality of men.

Following the death of Charles I, Cromwell became “Lord Protector of England” and took a vigorous role in stifling such emerging social directions. Under Cromwell, Puritanism became instead, in Hill’s words, “increasingly dour, dismal, and repressive”, the opposite of liberating. Following Cromwell’s unexpected death in 1658, however, radical movements revived quickly. After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, however, and the coronation of the high-powered Charles II, the new ruler took a central role in crushing them out again. Charles was also methodical and brutally effective in hunting down the men who had sentenced his father to death, even sending his agents to track down those who had fled to the New England colonies.

Cromwell’s body was dug up, publicly hung, and then beheaded. His head was then stuck atop a pole that remained outside Westminister Hall, the meeting place of Parliament, until following the death of Charles II in 1685, twenty-four years later. By the late 1600s, the currents so passionately embraced by the Levelers, Agitators, Diggers, and Ranters had been largely brought to an end. England moved instead toward even far greater class divides and disparities, combined with mounting decadence, debauchery, and depravity, as it headed into the 18th century and the beginnings of world-spanning imperialism.