Michael White, Isaac Newton: The Last Sorcerer, Basic Books, New York, 1997.

The execution of King Charles I by the anti-royalist Puritans in control of Parliament 1n 1649 was a dramatic watershed in English history. During the “Protectorate” of Oliver Cromwell and then his son that followed, the quest for new empirical insights and a more accurate understanding of the actual workings of the universe had declined sharply, enforced by Cromwell’s soldiers. To the Puritans, the divine revelation of God as set out in the Bible was what mattered, not the speculations of mere human beings. Along with the suppression of “fun” and of many specific kinds of recreation and pleasure, theological learning was emphasized instead.

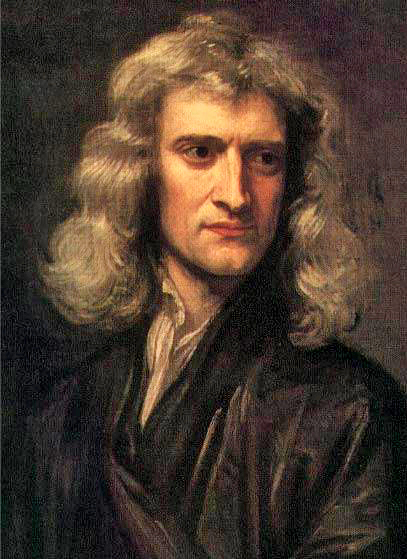

With the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, however, and the ascent of Charles II to the throne, all that was about to change. The imposing, lusty, energetic Charles II was a very different kind of man from his father. His own interests and the directions of exploration he encouraged ranged widely. The culture of England was about to transform again to virtually the opposite of how it had been during the decade-long interlude imposed by Cromwell and the Puritans. In 1661, the second year of the reign of Charles II, nineteen-year-old Isaac Newton arrived as a student at Trinity College, Cambridge from a small town in the north, so poor he needed to clean the rooms of more affluent students to pay his way. Even his undergraduate notebooks show a fascination with why the physical universe worked as it did and a search for sources that would expand his insight.

Increasingly, Newton came to see a central role for God, the Creator, in this unfolding. Encouraging him in this perspective was philosophy professor Henry More, the central figure among the “Cambridge Platonists” who viewed the world as permeated by an ethereal spirit they called the “Spirit of Nature.” The most important book authored by More was called The Immortality of the Soul. In 1669, at the astonishing age of only 27, Newton was named the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge. He had, however, already begun to lose interest in mathematics and increasingly shift his greatest focus toward alchemy, which sought to delve into the metaphysical realm where matter and spirit intersected and, from the perspective of the alchemists, interacted together.

Soon Newton was writing in his meticulously kept notebook that “there was no way (without revelation) to come to the knowledge of (the) deity but by the frame of nature.” Alchemy, he came to believe, might unveil the underlying fabric of the universe he was searching for. The wisdom embodied in alchemy seemed to derive from the most ancient times and eventually, Newton would come to own what may have been the most extensive collection of alchemical texts in all of Europe. Equally essential in the alchemical quest as specific knowledge, he maintained, was “purity of spirit” and leading a strict and disciplined life.

Newton wrote that in alchemy there was, “no real separation between the experimenter and the experiment, the qualities of one determine the outcome of the other.” The alchemical adept needed to be “pure of soul.” This was, he believed, “an absolutely essential feature of the art.” Newton became an early member of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. Today, the Royal Society still traces its roots to the semi-underground “Invisible College”, of which Newton was an early member. The true Invisible College, according to White, however, was the “network of nameless adepts who kept alive the alchemical flame.”

The sacred science embodied in alchemy, Newton maintained, could also be found hidden within the scriptures of the Old Testament, a central foundation also of kabbalah. A profound grasp of this heritage, he wrote, had, “made King Solomon the greatest philosopher in the world.” Through the “opening of metals”, Newton believed, they could ultimately be led to change their character and saw the seeds of this transformation as inherent in all matter. To Newton and others, this “primamateria”, was the “holy spirit of alchemy.”

Like many other intellectuals of the 17th-century, Newton embraced that, “the most ancient civilizations were also the most knowledgeable, the most pure, the most advanced.” He saw “unraveling the true past as his duty, including “alchemical history”, and was especially fascinated by the meaning of the geometry of Solomon’s Temple.

In 1672 Newton became a fellow of the Royal Society that now had the backing of Charles II. Architect Christopher Wren had become its first president and other members included chemist Robert Boyle, inventor, and scientist Robert Hooke, and diarist Samuel Pepys. Simultaneously he continued to pursue alchemical experiments in the well-equipped laboratory he had created in his rooms at Trinity.

The story of that pursuit and its ultimate outcome is set out in much greater detail in B. J. T. Dobbs, The Foundations of Newton’s Alchemy or The Hunting of the Green Lyon, Cambridge University Press, 1975. White acknowledges the importance of Dobbs’ work but does not restate it all here. According to Dobbs, after years of experimental effort Newton appears to have recorded in his notebooks that he had achieved refining and generation of the legendary “Philosopher’s Stone” and with its aid transmuted a quantity of lead into gold.

In 1695, at the age of 53, Newton left Cambridge to become head of the Royal Mint, then housed in the Tower of London. Under his administration, the Royal coffers began to swell. Did Newton’s self-described alchemical abilities play a role in this? Were they one reason he had been given that pivotal post? No author so far has dared to even speculate on this. It may, however, be more than a coincidence that the coffers of the British Crown grew steadily following the most renowned scientist in England, who also happened to be a practicing alchemist, being put in charge of the Royal Mint.

The final years of Newton’s life found him digging into the works of Pythagoras. He was striving for a deeper understanding of Pythagoras’ integration of musical harmonies with the larger order of the movement of the planets and operation of the universe, part of his ongoing quest to rediscover, unveil, and comprehend ancient knowledge.

Next: The Shadow of Solomon